Introduction

The October 2002 issue of The CrossFit Journal entitled “What is Fitness?” explores the aims and objectives of our program. Most of you have a clear understanding of how we implement our program through familiarity with the Workout of the Day (WOD) from our website. What is likely less clear is the rationale behind the WOD or more specifically what motivates the specifics of CrossFit’s programming. It is our aim in this issue to offer a model or template for our workout programming in the hope of elaborating on the CrossFit concept and potentially stimulating productive thought on the subject of exercise prescription generally and workout construction specifically.

So what we want to do is bridge the gap between an understanding of our philosophy of fitness and the workouts themselves, that is, how we get from theory to practice.

At first glance the template seems to be offering a routine or regimen. This may seem at odds with our contention that workouts need considerable variance or unpredictability, if not randomness, to best mimic the often unforeseeable challenges that combat, sport, and survival demand and reward. We’ve often said, “What your regimen needs is to not become routine.” But the model we offer allows for wide variance of mode, exercise, metabolic pathway, rest, intensity, sets and reps. In fact, it is mathematically likely that each three-day cycle is a singularly unique stimulus never to be repeated in a lifetime of CrossFit workouts.

The template is engineered to allow for a wide and constantly varied stimulus, randomized within some parameters, but still true to the aims and purposes of CrossFit as described in the “What is Fitness?” issue. Our template contains sufficient structure to formalize or define our programming objectives while not setting in stone parameters that must be left to variance if the workouts are going to meet our needs. That is our mission—to ideally blend structure and flexibility.

It is not our intention to suggest that your workouts should or that our workouts do fit neatly and cleanly within the template, for that is absolutely not the case. But, the template does offer sufficient structure to aid comprehension, reflect the bulk of our programming concerns, and not hamstring the need for radically varying stimulus. So as not to seem redundant, what we are saying here is that the purpose of the template is as much descriptive as prescriptive.

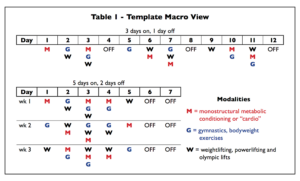

Template Macro View

In the broadest view we see a three-day-on, one-day-off pattern. We’ve found that this allows for a relatively higher volume of high-intensity work than the many others that we’ve experimented with. With this format the athlete can work at or near the highest intensities possible for three straight days, but by the fourth day both neuromuscular function and anatomy are hammered to the point where continued work becomes noticeably less effective and impossible without reducing intensity.

The chief drawback to the three-day-on, one-day-off regimen is that it does not sync with the five-day-on, two-day-off pattern that seems to govern most of the world’s work habits. The regimen is at odds with the seven-day week. Many of our clients are running programs within professional settings, often academic, where the five-day workweek with weekends off is de rigueur. Others have found that the scheduling needs of family, work and school require scheduling workouts on specific days of the week every week. For these people we have devised a five-days-on, two-days-off regimen that has worked very well.

The Workout of the Day was originally a five-on, two-off pattern and it worked perfectly. But the three-on, one-off pattern was devised to increase both the intensity and recovery of the workouts and the feedback we’ve received and our observations suggest that it was successful in this regard.

If life is easier with the five-on, two-off pattern, don’t hesitate to employ it. The difference in potential between the two may not warrant restructuring your entire life to accommodate the more effective pattern. There are other factors that will ultimately overshadow any disadvantages inherent in the potentially less effective regimen, such as convenience, attitude, exercise selection and pacing.

For the remainder of this article the three-day cycle is the one in discussion, but most of the analysis and discussion applies perfectly to the five-day cycle.

Elements by Modality

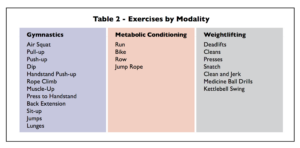

Looking at the Template Macro View (Table 1) it can readily be seen that the workouts are composed of three distinct modalities: metabolic conditioning (“M”), gymnastics (“G”) and weightlifting (“W”). The metabolic conditioning is monostructural activities commonly referred to as “cardio,” the purpose of which is primarily to improve cardiorespiratory capacity and stamina. The gymnastics modality comprises body-weight exercises/elements or calisthenics and its primary purpose is to improve body control by improving neurological components like coordination, balance, agility and accuracy, and to improve functional upper-body capacity and trunk strength. The weightlifting modality comprises the most important weight-training basics, Olympic lifts and powerlifting, where the aim is primarily to increase strength, power and hip/leg capacity.

Table 2 gives the common exercises used by our program, separated by modality, in fleshing out the routines.

For metabolic conditioning the exercises are run, bike, row and jump rope. The gymnastics modality includes air squats, pull-ups, push-ups, dips, handstand push-ups, rope climbs, muscle-ups, presses to handstand, back/hip extensions, sit-ups and jumps (vertical, box, broad, etc.). The weightlifting modality includes deadlifts, cleans, presses, the snatch, the clean and jerk, medicine-ball drills and throws, and kettlebell swings.

The elements, or exercises, chosen for each modality were selected for their functionality, neuroendocrine response and overall capacity to dramatically and broadly impact the human body.

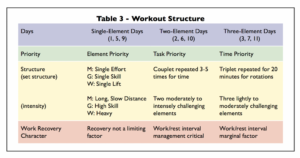

Workout Structure

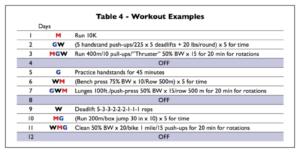

The workouts themselves are each represented by the inclusion of one, two or three modalities for each day. Days 1, 5 and 9 are each single-modality workouts, whereas days 2, 6 and 10 include two modalities each, and finally, days 3, 7 and 11 use three modalities each.

In every case each modality is represented by a single exercise or element, i.e., each M, W and G represents a single exercise from metabolic conditioning, weightlifting and gymnastics modalities, respectively.

When the workout includes a single exercise (days 1, 5 and 9) the focus is on a single exercise or effort. When the element is the single “M” (day 1) the workout is a single effort and is typically a long, slow, distance effort. When the modality is a single “G” (day 5) the workout is practice of a single skill and typically this skill is sufficiently complex to require great practice and may not be yet suitable for inclusion in a timed workout because performance is not yet adequate for efficient inclusion. When the modality is the single “W” (day 9) the workout is a single lift and typically performed at high weight and low rep. It is worth repeating that the focus on days 1, 5 and 9 is single efforts of “cardio” at long distance, improving high-skill, more complex gymnastics movements, and single/low-rep heavy weightlifting basics, respectively. This is not the day to work sprints, pull-ups or high-rep clean and jerk—the other days would be more appropriate.

On the single-element days (1, 5 and 9), recovery is not a limiting factor. For the “G” and “W” days rest is long and deliberate, and the focus is kept clearly on improvement of the element and not on total metabolic effect.

For the two-element days (2, 6 and 10), the structure is typically a couplet of exercises performed alternately until repeated for a total of 3, 4 or most commonly 5 rounds and performed for time. We say these days are “task priority” because the task is set and the time varies. The workout is very often scored by the time required to complete five rounds. The two elements themselves are designed to be moderate to high intensity and work-rest interval management is critical. These elements are made intense by pace, load, reps or some combination. Ideally the first round is hard but possible, whereas the second and subsequent rounds will require pacing, rest and breaking the task up into manageable efforts. If the second round can be completed without trouble, the elements are too easy.

For the three-element days (3, 7 and 11), the structure is typically a triplet of exercises, this time repeated for 20 minutes and performed and scored by number of rotations completed in 20 minutes. We say these workouts are “time priority” because the athlete is kept moving for a specified time and the goal is to complete as many cycles as possible. The elements are chosen in order to provide a challenge that manifests only through repeated cycles. Ideally the elements chosen are not significant outside of the blistering pace required to maximize rotations completed within the time (typically 20 minutes) allotted. This is in stark contrast to the two-element days, where the elements are of a much higher intensity. This workout is tough, extremely tough, but managing work-rest intervals is a marginal factor. Each of the three distinct days has a distinct character. Generally speaking, as the number of elements increases from one to two to three, the workout’s effect is due less to the individual element selected and more to the effect of repeated efforts.

Application

The template in discussion did not generate our Workout of the Day, but the qualities of one-, two- and three-element workouts motivated the template’s design. Our experience in the gym and the feedback from our athletes following the WOD have demonstrated that the mix of one-, two- and three-element workouts are crushing in their impact and unrivaled in bodily response. The information garnered through your feedback on the WOD has given CrossFit an advantage in estimating and evaluating the effect of workouts that may have taken decades or been impossible without the internet.

Typically our most effective workouts, like art, are remarkable in composition, symmetry, balance, theme and character. There is a “choreography” of exertion that draws from a working knowledge of physiological response, a well-developed sense of the limits of human performance, the use of effective elements, experimentation and even luck. Our hope is that this model will aid in learning this art.

The template encourages new skill development, generates unique stressors, crosses modes, incorporates quality movements and hits all three metabolic pathways. It does this within a framework of sets and reps and a cast of exercises that CrossFit has repeatedly tested and proven effective. We contend that this template does a reasonable job of formally expressing many CrossFit objectives and values.

About the Author: Greg Glassman is the Founder of CrossFit Inc.

Reference link:

https://journal.crossfit.com/article/a-theoretical-template-for-crossfits-programming-2